I grew up in the Midwest in the 1950s and ’60s. At that time violence against women was so ordinary that a gangbang (as in a group of men having sex with one woman) was just something guys did — not all of them, not by a long shot, but it wasn’t something to hide, even if the young woman had been raped, unless you happened to be that woman (because she must have been ‘asking for it’ — why else would she be alone with a bunch of guys?). A woman who ‘pulled a train’, willingly or not, was called a ‘hog’ — the same word bikers used for their Harleys, only the connotation was negative, not neutral. Date rape wasn’t even a blip on the radar — not that it didn’t happen, but there were no words for it. No one talked much about domestic violence, either; having an abusive husband was regarded as bad luck or a woman making a poor choice, even while women had very little choice — no legal rights over their own bodies if they got pregnant, since abortion was illegal, no battered women’s shelters, few job opportunities (teaching or nursing if you could afford that level of education; secretarial work; otherwise waitressing, housekeeping, retail, or factory work were about it [in urban areas, anyway]), and forget equal pay for equal work, or good, affordable childcare. Meanwhile, movies presented women as damsels in distress, to be rescued or not, if they were foolish enough to wander around at night alone, or unfortunate enough to be caught by a bad guy. Even after the rebirth of feminism in the late ’60s women continued to be portrayed as victims, and that portrayal was presented as ‘normal’, which was a form of violence in itself. If we learn from the stories we are told and the images we see (laying down neural pathways in the brain), then movies until then had taught women how to be terrorized and helpless in the face of danger, how to be hurt or killed without putting up a fight.

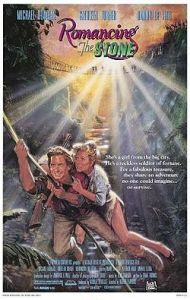

The first movie I saw that showed a woman fighting back and winning was Romancing the Stone, which came out in 1984.* I mean fighting back and winning physically; right now I’m not interested in the spiritual work of forgiveness, but the visceral thrill of revenge. Diane Thomas wrote the screenplay, about a romance writer in NYC named Joan Wilder (played by Kathleen Turner) who goes to Colombia to rescue her kidnapped sister, and encounters perilous adventures like the ones she’s been writing about in her wildly popular books.

Romantic comedy; but at the climactic scene no one is laughing. Joan Wilder is lying on her back on a wooden grating over a crocodile pit and the villainous Colonel Molo — with a lit cigar between his teeth and a bleeding stump where his hand used to be — is on top of her, holding her down and ready to commit murder. Even one-handed he has her pinned; she can’t reach the stick of wood that is the only weapon in sight. Joan is hoping that Jack (her hero, played by Michael Douglas) will save her, but he can’t get up the stone wall to where she is; he’ll never reach her in time. Below her the crocodile thrashes his tail — having had a taste of the bad guy (Molo’s hand), the crocodile wants more. (A lot like Captain Hook, which makes Joan the Peter Pan of this story.) As Molo snarls and leans toward Joan, the lit cigar getting closer to her eyes, she suddenly yanks the cigar out of his mouth, turns it around, and stabs the lit end into his face. He rears back screaming; she flips over sideways, grabs the stick of wood, and smacks his bloody stump hard. Howling, he turns, falls, and breaks through the wooden grating, down to where the crocodile waits.

This wasn’t the end of the movie, but it was definitely the high point. When I first saw the film nearly every woman in the audience was leaning forward and shouting encouragement to Joan, something like, “Hit him! Kill him! YES.”

It was one of those great movie moments. (Interesting that the studio thought the movie would bomb.) Asking around later, I found that every woman I knew had had that same response — total adrenaline rush, followed by laughter. Not embarrassed laughter, but delighted laughter. Because it was about fucking time.

*There have been other movies before that time to show women fighting back and winning. The movie version of Modesty Blaise came out in 1966, and there had been women TV characters, like Emma Peel, who could take down male opponents. But the Modesty movie was ‘an outrageous spoof’ and Mrs. Peel was spy-fi; they were fantastical. You couldn’t identify with them any more than a man could identify with 007 or Dr. Who. Also, I’m not a film buff, so while there may have been an earlier ‘ordinary’ woman who fought back and won, this will only be about what I noticed in my own ‘ordinary’ movie-watching.